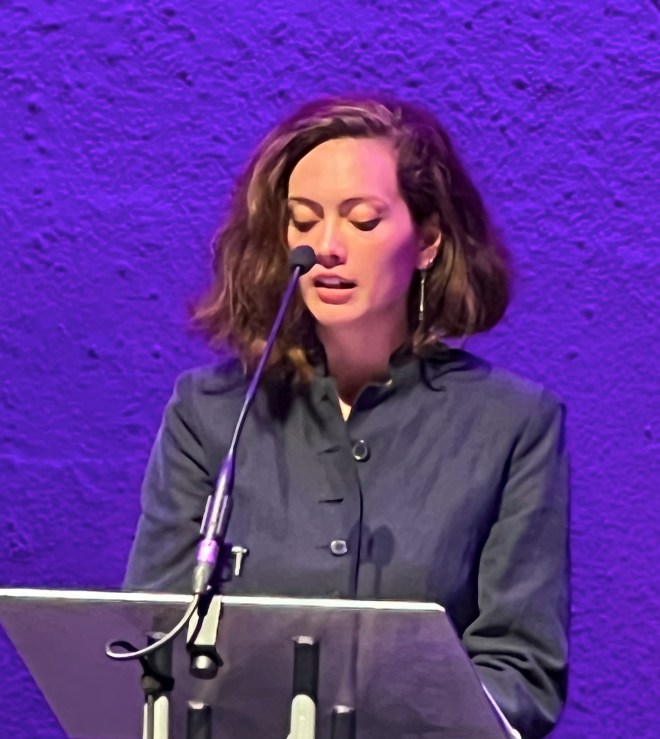

A selection of photographs of local poet Simon Maddrell. PHOTOGRAPHY BY DIENSEN PAMBEN.

Two or three years ago, on a warm, late summer afternoon, Simon Maddrell and I met on the South Coast of England, just along from Brighton. The sea was a flat lustre of gold and blues, barely moving, the tide beginning its slide out towards France. With the air tickled by the faintest breeze, we drank at a beach cafe, sitting on the shingle among barbecuing families, then set out with my dog Ithaca on a long, slow meander along Worthing’s gritty sand, skirting between tide pools, looking for hag stones and beach treasures for Simon’s Brighton garden, and flints and sea-shaped chalk for my desk in London. As we scanned and walked together, comparing finds, pointing things out to each other, the sea always beyond us, the sky huge and wide, we felt an ease of familiarity growing, recognising the mutuality our shared of experiences of London in the early 1980s, when HIV and AIDS were visited upon the queer communities in which we moved, and comparing notes on coming to write poetry in our fifties, and why each of us had needed time to arrive at voices that would hold our complex subjects. That conversation is still flowing. It is the greatest pleasure to bring some of our words to the page — as Simon publishes a long awaited debut collection, after a string of stirring pamphlets, on both sides of the Atlantic. The photos which flower between our words were taken by Simon Maddrell in their salvaged, cherished Brighton garden — from which many of the poems grow.

ah: Let’s start with the big news. Your debut collection, lamping wild rabbits, is published by Out-Spoken Press in February 2026, edited by the legendary Anthony Anaxagorou. Tracing the rainbow arc of your life, you begin by exploring being born queer and Manx at a time when homosexuality was still illegal on the Isle of Man (IOM). The poems ask how a person can be, and grow, if their deepest self not only is prohibited, but also punished in law? It’s still a live, and lethal, issue in many countries around the world. Is the personal inherently political for you?

sm: lamping wild rabbits with Out-Spoken Press is my best poetry dream-come-true. Anthony was the first poet/teacher to encourage me, even as he gently demolished six of my earliest poems at a Poetry School one-on-one session! (I looked it up; it was March 2nd, 2019). He has been a mentor and teacher of mine at various times ever since, so it was wonderful for him to be so effusive about my collection manuscript, and then to work with him to craft the final book. It’s such a privilege to be part of the Out-Spoken stable, and I hope its reception does them justice.

Talking of justice and the ‘personal as political’ –– our mere existence is political, and for too many of us, who we are personally is an existential threat. Of course, my personal existential threat is not what it was 40 years ago, but lamping wild rabbits shares some of that experience, and some who didn’t make it. Even if childhood traumas are personal, they soon become political e.g. how the social service system fails to support victims of child abuse.

It must be said that whatever existential threats I have endured, they don’t compare to the fears many trans women have walking down the street today; the ten miles that women in Africa walk for water daily to sustain their families; the 24/7 drones in Gaza that are even felt by deaf children, never mind the horrors that are inflicted upon Palestinians. The collection does reflect on these more collective threats, and I firmly believe that the ‘personal and collective’ are allowed to sit alongside each other, rather than in competition, or even comparison, with each other. There is neither competition nor comparison in these things.

When I think of the times of my youth, they are deeply affected by the Greater Manchester Police GMP) Chief Constable James Anderton and his assistant Robin Oake, who exported their homophobic policies to the IOM in 1986 –– harassment, entrapment, and inequitable law enforcement that cost lives. My youth was shadowed by these direct & indirect threats, like The Bolton Seven who were arrested & convicted for consensual sex, Anderton buying a cruise boat with a spotlight to catch men kissing under bridges on Canal Street, Manchester, him epitomising people with AIDS as ‘swirling around in a human cesspit of their own making’, and Oake’s illegal entrapment and forced confessions of gay & bi men in the IOM in the late 80s/early 90s (Brilliantly portrayed in the short film No Man Is An Island). I think when a serving Chief Constable says, as late as 1987, that “sodomy between males…ought to be against the law” it is difficult to not see the personal as political.

ah: Your opening poem strikes a sombre note, while simultaneously upholding a movement of hope and transformation. It begins

it’s as though

we have to climb

out of our damage

up an invisible rope

and apologise.

a rope we’ve been carrying

all our life

That determination to give witness, alongside a refusal to be defeated, appears central to your creative impetus. Is that how you experience it?

sm: I believe that ‘bearing witness and a refusal to be defeated’ are central to my life’s impetus, but only a part of my creative one, if I am understanding the question correctly. As will hopefully be apparent in discussing my pamphlets and the collection, I feel the central impetus to what I write is varied. Of course, as with most early-stage writers, I began with the autobiographical in the way your question describes. Queerfella was “my journey from shame to unashamed” and hence central to the creative impetus. One might say section one of lamping wild rabbits, ‘caged rabbits’, is just a better version of Queerfella, but I hope people experience it as more than that. I think at other times, the creative impetus is more subject-driven, whether that be queer history, queer biography, the ambivalence of an exile, or the Isle of Man as a place (even if, like Penny Lane, it ‘is in my ears and in my eyes’). Whether that does or doesn’t include my direct experience is just a consequence of how to best explore the subject, rather than it being central to it, or even necessary to it.

ah: Going back to you beginnings as a poet – your first publications were the pamphlets Throatbone and Queerfella in 2020. I believe they found their way into print along two very different pathways?

sm: Throatbone did have an unusual birth. The Raw Art Review, a Massachusetts magazine, published a couple of Manx poems in Summer 2019. In December 2019, I was shortlisted for their Poet-in-Residence. The editor, Hank Stanton, loved the Manx poems I had submitted, so I asked if I could pitch the pamphlet draft, Throatbone, in January, which he accepted (thanks also to the mentoring support of Anthony Anaxagorou). The Manx heritage organisation, Culture Vannin, funded 300 copies for me to sell over here –– I just sent the last copy to the British Library!

Joelle Taylor mentored me to improve Queerfella, but it was rejected by four publishers before eventually jointly winning The Rialto Open Pamphlet Competition 2020 alongside Selima Hill’s Fridge –– the latter being a particularly surreal fact.

ah: Since then, you’ve published The Whole Island and Isle of Sin, which grow out of the intersections of your Manx heritage and out and proud queer identity, and the history informing both. Tell us about these two books.

sm: Even though Isle of Sin was published first, in Feb 2023, it came as an overspill from The Whole Island, which I wanted to be an exploration of what I later realised was an ambivalence about the IOM, albeit an ambivalence of joy & sadness rather than love & hate. The central titular (but in Manx Gaelic) poem was inspired by Virgilio Piñera’s long poem La Isla en Peso, 1968. Whilst this is usually translated as The Whole Island, literally it means “the weight of the island”, which to me, more poetically encapsulates both poems. The Whole Island explores the ambivalence of a returning exile, rather than someone ‘stuck there’ but also explores the place, the island as a body, the body as an island. The Whole Island was funded by the Manx sister to the IOM Arts Council –– Culture Vannin, and published by Valley Press.

In embarking on this, I found myself also reflecting more on the dark days of the police harassment and entrapment of gay & bi men in the late 1980s. I’d done this in a poem sequence in Throatbone, but was now driven to transform that anger into activism and, to be frank, mockery. Consequently, I was involved in lobbying the IOM Police for an apology (they became the first police force in the British & Irish Isles to apologise for the way they treated people like me). This also coincided with It’s A Sin when I became aware of Manx actor Dursley McLinden –– who was one of the inspirations for Olly Alexander’s character, Richie Tozer –– and how he had been mostly erased from history (I performed at the launch of the first-ever queer exhibition at the Manx Museum and he didn’t even appear anywhere). After all of these diversions, I ended up with too much for a pamphlet, and as I didn’t want to do a first collection yet, I developed a manuscript for Isle of Sin –– including improved versions of the Throatbone sequence –– and approached Peter Collins at Polari Press who I knew was keen to tell queer stories.

ah: A more recent publication, on the thirtieth anniversary of Derek Jarman’s death, is the wonderful, intensely moving, a finger in derek jarman’s mouth, with Polari Press. How did this project come together?

sm: Derek Jarman is an overwhelming inspiration, not in the least because of his response to being diagnosed HIV+ and his ‘return’ to the coast and creating a garden out of nothing, which inspires mine. I re-immersed myself in Jarman, in particular his time (and garden) at Prospect Cottage, along with the Protest! exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery, plus the ones at The Garden Museum, London and John Hansard Gallery, Southampton. I found myself writing voraciously about him –– or perhaps more accurately –– about HIV, mortality and connection to nature.

a finger in derek jarman’s mouth was turned down by nine publishers (longlisted by only one) so I approached Polari Press about the idea of a series of three pamphlets over three years, with the third being Patient L1 in Feb 2025 (more of that later). I also knew that Peter liked the idea of doing a boarded-cover limited edition at some point, so I pitched that too –– we sold out the 130-copy limited edition before publication date, and Peter deservedly won the Michael Marks Award for Best Illustrated Pamphlet in 2024 –– for the cyanotypes that feature in both editions.

ah: If we ever needed someone to defend the values of persevering, and always trying another route if the obvious path is blocked, you would be that person Simon! Ideas of continuing, and persisting, and creating things which will resonate beyond our lifetimes are at the heart of your relationship to Derek Jarman as you have told us. In the last but one poem, ‘dear derek jarman’, you write

you refused to die without the sun

rising without stones threaded

and hung in a garden that grew out

of nothing, without going quietly

smiling in slow motion like an iceberg

sinking from the sky, the ripples still

licking shingle in a one-way tide.

These lines hold for me the coalescence of life in death, and life despite death, which contribute powerfully to the book’s magic. Could you say something about them?

sm: As I mentioned, engaging with Jarman is an exploration of mortality, and while you capture it, I’d perhaps say ‘life despite impending death’ and the reckoning with the truth that ‘impending’ is true for us all, not just those with a terminal illness. I think for me, life felt like a terminal illness until I accepted my queerness as a ‘gift’ (if that doesn’t sound too glib). Jarman helped me do the same with HIV –– “as if being banned and disliked is a pinnacle after all” (‘dear derek jarman’). I think ‘giving life’ is part of the human condition, and for queers of my generation, ‘offspring’ wasn’t an (easy) option, but gardens are! Perhaps, the older we get, the more we see life, like Dennis Potter’s whitest, frothiest, blossomest blossom that there ever could be.

ah: That’s a wonderful way of seeing things Simon. I concur, wholeheartedly, in full blossom! Thinking more into the connections between you and Jarman, refracted dualities are at the heart of a finger in derek jarman’s mouth, which adapts its title from Jarman’s collection a finger in the fishes mouth. You are, and Jarman was, both out and HIV positive with all the difference that three decades make in terms of effective treatment protocols. In speaking queerly with him, through blurred and echoed reflections and transmissions of his artworks across multiple media, was part of your intention to explore how, without invoking biological intergenerationality, we all live through and beyond time, through our enduring vibrations within the lives of others?

sm: I’m not sure I am capable of intentions that grand –– or that well-thought through, but now you say it, I do think that’s what the book does. I guess I’m primarily a practical man –– so decide to ‘do things’ wholeheartedly, and it is through that whole-heartedness that something deeper emerges, something you can arguably only realise or discover in hindsight, rather than plan for in advance. Also, if Jarman creates ‘enduring vibrations within the lives of others’, as I feel he does, then those vibrations are there anyway –– rather than requiring exploration, they need expression.

ah: By working so strongly through multi-gendered transitory experiences – flowers, gardens, weather, sex – the poems give off this heady summer heat, and with that the sense of being a memorial to a whole generation of people of both genders dying in the prime of life from HIV/AIDs before treatment became available. While Europe and North America saw a predominance of male deaths in the first wave, in Africa and beyond, gender was not a factor in transmission and infection. Was that an interest of yours?

sm: With a finger in derek jarman’s mouth being a tribute to Jarman then to me the focus of the book was to reflect his UK experience of HIV/AIDS, as you say “the sense of being a memorial to a whole generation”. But also, what he said and role-modelled in terms of confronting HIV stigma, and how that is even more important today.

But worldwide HIV/AIDS is absolutely an interest of mine. I get frustrated when queer people and organisations talk about HIV/AIDS as though it is a thing of the past. (For heaven’s sake even The Guardian refer to it as “Aids” for that very reason). It is still a global epidemic. Not only is HIV/AIDS a real, and growing, problem here, but it is even more of a problem in the USA due to lack of blanket access to medication, and even more of a problem overseas, especially in Africa. Africa has 50% of new infections, and the latest Trump attempts to block US-funded medication for Africa would be catastrophic.

630K people died of HIV-related causes in 2024. WHO is only targeting this to decrease to 400K by 2030. Can you imagine if WHO had said that about Covid?

ah: The physicality of Prospect Cottage, and the shoreline at Dungeness, moves like a blessing through the poems. They are good places where the reader can seek imaginative refuge, as Jarman did. At the time of writing you had yet to visit. How did you make the site feel so real?

sm: I am an island boy, and had also moved to Brighton in early 2020 with its shingle beaches. Like Jarman I collected hundreds of hag stones from the beach and hung threaded ones from trees, or on spikes, in the garden. A garden I was creating inspired by Jarman, albeit mine had four walls rather than none, and some of the jetsam is from the street not the beach! I also immersed myself in his books and the amazing derek jarman’s garden (Thames & Hudson, 1995). There was also a wonderful exhibition, replicating the cottage at The Garden Museum in London. The gateway technique, of course, is to focus on capturing the emotions of it all. The technical facts are easy in comparison, but still crucial as we are reminded in William Blake’s “holiness of minute particulars“.

ah: The photos you gave given us from your garden, which blossom through our conversation as moments of ecstatic, transient, green beauty enact what you say, Simon. More soberly, since COVID, the whole world has discovered what it’s like to become vulnerable to a new virus. You and I both remember the onset of HIV/AIDs at first hand, and its early ravaging of queer communities in the UK.

Like COVID, HIV/AIDS offers us the chance to look at natural evolution in the raw, with all its extraordinary potential for mutation. In ‘powered by HIV’ you write of

an overactive fuel

energy from atomic

cell destruction

Did this terrifying energy also run through these poems as a paradoxical creative source?

sm: I saw radioactive destruction as a metaphor for HIV and saw, as Jarman did, HIV as a creative energetic force –– driving the imperative to explore and accept mortality. Radioactivity is of course a paradox in itself –– giving energy, curing cancer and giving us a toxic legacy for generations, and in that it is not alone. In many ways, there are other ‘terrifying energies’ we face as human beings, especially the ‘others’ and ‘less powerful’ amongst us, and that certainly fuels what I want to say and explore. It is probably fair to say that the toxic energy and impacts of shame are very predominant in the collection, as is the power of redemption.

ah: Both energies pulse through the poems. You have mentioned that in Europe and North America the most deadly aspect of HIV/AIDS is the stigma that is still attached to it, and the consequent reluctance of people to come forward even when they suspect they may have symptoms, or have simply had an unprotected sexual encounter which should logically point to the need for testing. Could you say more about this perceived stigma, as the statistics, and their consequences, are something people need to be more aware of.

sm: I don’t think stigma is perceived, but there are two types– the stigma attributed and directed by others, and the stigma we impose on ourselves, HIV stigma, both of which negatively impact male suicide rates (and also female suicide rates in Scandinavia). According to a study published in The Lancet, the male suicide rate is five times higher than average in the first year after diagnosis and twice as high overall. Of course, we know how high male suicide rates are for men already (especially for those 18-30 and 45-60). The reason that the study concluded that the prime cause was stigma was that the rates were unchanged between 1996 and 2012.

I would argue it is the prime cause of the fact that more people are now diagnosed with HIV in the UK through heterosexual sex than ‘men who have sex with men’ (MSM), and even more crucially, why late diagnosis is significantly higher for straight men and women, compared to MSM (70%, 50%, 30% respectively). Of course, late diagnosis means that it is highly likely that more people have been infected per diagnosis, and that the risk of suffering life-long or life-threatening illness such as PCP is much greater. Someone died of HIV-related illness in Brighton last week.

Stigma was something that Jarman recognised, which is why he was the first ‘famous’ person to declare his status in late 1986. Greater openness is a key to breaking down stigma, but so are public attitudes –– hopefully helped by HIV no longer being a “lethal weapon” carried by those successfully managed on medication. In my own case, I realised in the 2-3 years after diagnosis that I risked being locked into another closet, and more so reinvigorating that ‘voice of shame ‘ telling me I was worthless and ‘being what I deserved’. To counter the championing of openness, it is important to acknowledge that English Protestant culture, and many of the other cultures here, don’t really approve of talking about sex, and the fear of being considered queer is more prominent than one might expect.

ah: In the ‘feral rabbits’ section, a short sequence of sexy, razor-sharp, poems rush the reader into a space from which safety abruptly exits. We get to feel-along with what it might be like to find yourself with an HIV positive diagnosis. How did these poems come together? They feel brave, intimate, and honest, but also deeply crafted and deliberately made – acts of beauty that refuse shame.

sm: I’m really pleased that is how you read and saw the poems. The three poems, ‘Private Members’ Club, ‘The first sex party…’ and ‘Did he…?’ were originally written as a triptych (I honestly can’t remember why they now aren’t!). I wrote them over a relatively short time period, but ten years after my diagnosis (and after a finger in derek jarman’s mouth, which may be relevant or significant). For years, I’d found it impossible to write about the specifics of my HIV contraction or diagnosis, or about navigating the trauma. There are so many pitfalls, and at least three mineshafts to fall down — and I know you’ll forgive me, but I won’t name them as they do not warrant being ‘invited in’ for scrutiny. Those three poems were definitely the hardest poems to write in the whole collection, so it makes me very proud when you, and especially you, say they are “deeply crafted and deliberately made”. They were poems I knew I had to write, there would have been an elephant-sized hole in the collection without them, whether anyone else would notice or not.

ah: More practically, would you be able to share a few words about your experience of being supported by healthcare providers on this journey, in the event that someone who reads our conversation is fearful of being judged if they come forward for testing?

sm: HIV doesn’t discriminate, and neither, almost without exception, do healthcare professionals, who are also bound by professional confidentiality. Self-test kits are now available, albeit I would recommend going to a clinic if you feel there is a high chance of diagnosis so that you get the excellent support they offer. I have taken PrEP twice, which you usually get via A&E rather than the specialist health workers –– on both occasions, I was thanked by the doctor for coming in and taking it. My dentist didn’t bat an eyelid and I am unaware of any actions they take which make me feel stigmatised (e.g. the ‘end of day appointments’ of yesteryear). I had my ear pierced the other week and I told them. The response? “Oh, that’s fine! I don’t think we are even allowed to ask you that nowadays! It makes no difference, but thank you for thinking about it.”

ah: Life lived alongside HIV is also a theme within the poems that you have co-created through conversations with actor, activist, artist and tailor Jonathan Blake. They have so far been published in your Polari Pamplet, Patient LI, which you and Jonathan have performed from together, but this is just the beginning.

sm: In 2019, I approached Jonathan Blake (who was played by Dominic West in the film, Pride) about writing his life story in poetry. He was diagnosed with HIV in 1982 ––known as ‘Patient L1’ at London Middlesex Hospital. He is now 76 years old. I have done over 50 hours of interviews with Jonathan and I also have access to 4.25 hours of interviews done by the British Library in 1991.

Thanks to Arts Council England, Polari Press published a pamphlet version of Jonathan’s story, Patient L1, in February 2025. Jonathan read poems at the launches, which included found poems from a journal Jonathan’s partner of 39 years, Nigel Young, wrote on a holiday in April 1985. The poems went down so well, we published, under Nigel’s Septum Press, Jo & Ni Go Cruising in July 2025 –– thanks to Andrew Lumsden’s Grand Camp Maisie Fund.

Work continues on the full book, which is a mixture of prose in the writer’s voice and verse in Jonathan’s voice, provisionally entitled, The Life of Jonathan Blake in Twelve Acts –– with a Prologue, Interlude & Epilogue. Its length and complicated categorisation will make finding a publisher difficult, but sure we’ll get there.

ah: I have both books, and cherish them. I also really valued hearing you and Jonathan Blake reading the poems together. His story, through your and his words, in both of your voices, is a compelling and miraculous enactment of what co-creating can engender. That’s a pleasure to come, but let’s close for now with lamping wild rabbits. Having had the privilege of reading a press proof, I know that ‘dead rabbits’ is the last section, albeit that these poems are uncompromisingly full of life. Tell us a little more about them, and also what leads into this final act.

sm: Death, and hence mortality, is such a taboo, but I find exploring it strangely reassuring. For me, I can’t have lived through the last two years without meditations on mortality broadening to what it is to be human, broadening into considering the deaths that we are seeing every day –– especially those under the shadows of war crimes & genocide.

lamping wild rabbits hinges or pivots around the central ‘dungeness rabbits’ –– a tribute to Derek Jarman’s responses to his HIV diagnosis, with nine poems from the pamphlet. The book begins with ‘caged rabbits’ –– arguably a better version of Queerfella escaping shame and embracing freedom while ‘feral rabbits’ confronts the trials and tribulations of escaping the ‘domestication’ of sexual oppression. ‘wild rabbits’ is my response to HIV, inspired by Jarman connecting gardens & nature.

I’m excited about it. Outside of the Jarman section there are only seven poems from my pamphlets leaving over 50 poems –– half of which have never been published anywhere else.

ah: I know that readers will be as blown away by them as I have been, Simon. For people who want to order a copy, or attend a reading, the links are here.

Website:

Order from Out-Spoken: www.outspokenldn.com/shop/rabbits

Signed Copies: simonmaddrell.sumupstore.com/product/lamping-wild-rabbits

Launches & Readings

(Up-to-date events and ticket links at linkin.bio/simonmaddrell/)

Launches

London

Thurs 12 Feb Betsey Trotwood, EC1R 7pm

with Kostya Tsolakis

Brighton

Thurs 19 Feb The Walrus, Ship Street 7pm

with Naomi Foyle & Robert Hamberger

Manchester George House Trust Fundraiser

April Queer Lit Bookshop 7pm

Readings

Common Press Bookshop

Sun 22 Feb Bethnal Green Road, E2 7pm

with Nathan Evans

Milton Keynes Lit Fest

Tues 24 Feb Online 7pm

with Julia Bell & Len Lukowski

Yer Bard Poetry

Wed 18 March Dash The Henge, SE5 7pm

with Jake Wild Hall

Kemptown Bookshop

Thurs 26 March Kemptown, Brighton 7pm

with Ken Evans & Luke Kennard

The Elephant in the Room

Tues 31 March Online 7pm

Cork International Poetry Festival

Fri 15 May Cork Arts Theatre 7pm

‘The HIV Readings’ Fundraisers

Brighton: Lunch Positive

Thurs 12 March The Queery Bookshop & Café, 7pm

with Jonathan Blake & Robert Hamberger

London: UK AIDS Memorial Quilt

Fri 13 March, 7pm

The Devereux, Temple WC2R

hosted by Jonathan Blake, Patient L1

www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/the-hiv-readings-in-aid-of-uk-aids-memorial-quilt-tickets-1981421186106

Simon Maddrell Social Media

Website: simonmaddrell.com

Facebook Page: @SimonMaddrellPoetry

Facebook Personal: @SimonMaddrell

Instagram: @simonmaddrell

Bluesky: @simonmaddrell

Threads: @simonmaddrell