Some blogs begin upbeat. Others have to work their way towards hope. This falls into the second category. But stay with me, and we’ll travel towards a light of reclamation together. Like most of you reading this, I’ve never been bombed. I’ve never had to leave my home and live in a tent in a refugee camp. I’ve never fallen asleep on the ground not knowing whether the people I love will be killed as we sleep. In some ways, there is a gulf of uncrossable distance between me and the Palestinians who are being subjected to genocide by the current Israeli government in Gaza.

But in other ways, less so. That is, I have some insight into aspects of what Palestinians may be going through. Partly as a result of reading the firsthand accounts that people are managing to get out of Gaza and following videos and news reports. But also because my late father-in-law, the sculptor Oscar Nemon, lost twenty-four family members to the genocide of the Holocaust during World War II, including his mother, his brother and his grandmother. The man I met in 1980 had lived by then for forty years in the shadow of that loss, and been transformed by its absences. The drawing below is a mourning sketch by Oscar Nemon, as is the image at the top of the blog, written on a ‘Don’t Forget’ notepad which he used more than once for these memorial sketches.

The German branch of my own Messel family of origin was similarly truncated by genocide. As a teenager in the 1970s, I visited two elderly relatives, an architect and his wife, who had escaped from Berlin during the 1930s, and by then lived in Swiss Cottage. Like my father-in-law Oscar Nemon, almost all their family members were transported to their deaths by the Nazis as a result of having been identified by the Third Reich as Jewish.

I also have some understanding of the longer term psychological consequences of what is taking place in Gaza. This comes from my own history of growing up being subjected to the powerlessness, and violence, of childhood sexual abuse. For these reasons, and because I am a human being, it haunts me to know the current Israeli government has chosen to put a neighbouring nation in hell – and keep them there, with long-reaching intergenerational consequences, even beyond any ceasefire.

In mid-February 2024, preparing to read as one of three headline poets at the legendary Verve Festival in Birmingham, with the brilliant, ferocious Nicole Sealey and Rebecca Goss, the Palestinian fight for life and freedom has been very present to me, as it has been to so many of us. Drafting the text I planned to read, I continued to follow news updates and saw the horror worsen by the day, as food supplies in Gaza became even more insecure, notwithstanding the trucks lined up and ready to deliver essential aid at the border.

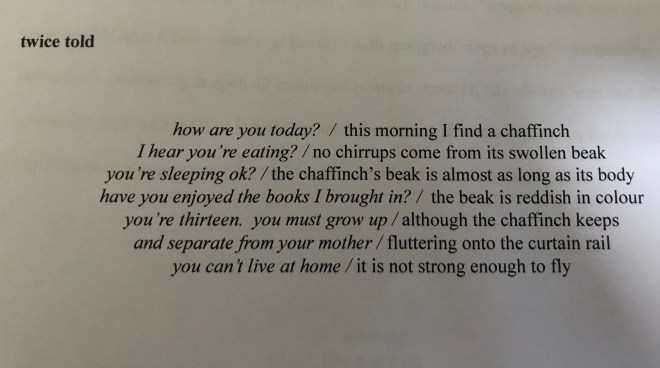

With this in mind, I built my set from bird of winter to explore ‘words as pathways to freedom’ from poems which held both my own childhood experiences, and references to the current occupation of Gaza. I wanted Palestinians to be honoured, and kept with us, through every word I said in Birmingham’s Hippodrome Theatre. I needed the progression and evolution of my child self from oppression and injury through to reclamation and freedom also to articulate our and Palestine’s hopes for their nation.

During the week before Verve, writing and redrafting my linking words, rehearsing the chosen poems, I started to re-experience childhood injuries arising from the abuse like those described in ‘remnants/silvae‘, which you will see below. Through them, my adult body expressed its memory of what had been done to me fifty years earlier. Rather than backing off, I kept redrafting and rehearsing, while also take time out to safe-guard myself and swim. I recognised the oppression that had overwhelmed me when I was too young to refuse it, but knew I was managing it as a side-effect of generating the possibility of transformation and healing.

As I took the train up to Birmingham on Friday evening, where I was also going to lead a workshop on colour for Verve on the Sunday, a violet wash of sunset illuminated the dregs of the ending day. The sky seemed to sing hope and promise to the muted greys and the greens of the winter landscape.

I took this as an omen for my Saturday performance with Rebecca Goss and Nicole Sealey, hosted by fellow poet and former archaeologist Jo Bell. The next morning, after catching Holly Pester’s brilliant Verve/ Poetry School lecture, I carried my script for the evening to the canal side, and sat on a bench in the sun rehearsing quietly. I asked for the day’s energy to illuminate the darkness in which Rebecca, Nicole and I would perform together, and bring from it light.

The words which I shared with a packed theatre space in Birmingham, on 24 February follow. What Rebecca Goss and Nicole Sealey read was no less searing, as you’ll see if you follow the links here through to their work. Rebecca’s poems illuminate what it can mean to lose a child, and then and live beyond that loss. Nicole’s ask us to face how institutional racism wounds, and that it destroys not only individual lives, but also the societies from which they grow.

As you read my own words spoken in the Hippodrome Theatre, which follow, imagine me swinging a sacred sistrum out over the audience to initiate the poems, then overarm-bowling a red rubber ball among them to be chased by the resurrected ‘dog of pompeii’. At the end, as ‘vesuvius’ closed, I joined my palms in a gesture of prayer, raising them up to eye-level, and then opening my arms out to form the branches of a tree, symbolising new growth and a healing future for all of us in the theatre and beyond.

words as pathways to freedom

alice hiller Verve Poetry Festival, 2024

Thank you for inviting me to Verve. It’s heartening to be here, particularly at such a hard time, as we witness the genocide underway in Gaza. Like many of us making our lives beyond trauma, I rage, and grieve, that what is taking place under the Israeli invasion will continue to impact the Palestinian people for generations, even after their land is restored. I have chosen poems whose imageries stand in solidarity with their fight.

When I speak of ashes and rubble, of ‘entombed cities’ and ‘absent peoples’, let your thoughts go also to Gaza. When I ask that our streets may be ‘muffled with mourning’ think of their streets also. But when I speak of growth and reclamation, be with Palestinian peoples, who are fighting for their own secure future.

For all of us facing hardships, even on a lesser scale, words open pathways towards freedom. I hope to share one aspect of this process tonight, through the poems of bird of winter. They respond to my experience of sustained sexual abuse in childhood, but also of finding healing beyond a crime that impacts millions of us around the world. Whether in therapeutic, creative or social contexts, arriving at language that can hold and release trauma is, of course, tough.

To speak, we may have to re-enter spaces of near annihilation, and reclaim the selves and memories we left behind in order to survive. Recognising the real dangers this represents, my work also plays out the opposites of what I was subjected to. Where I was without agency, my poems summon it. Where I was left in darkness, I claim light. Where I was hated, I counter this with love for the child and the teenager I once was, and the woman we have become.

Because I want the collection to perform acts of resistance, and restitution, as well as witness, bird of winter interleaves the sexual abuse by my mother, and its aftermath, with poems honouring what allowed me to come through. I also celebrate the nurture I received, and still receive, from the world around me, having turned outward towards it very young, with no secure home for shelter.

In bird of winter, this sustaining communion is channelled through found materials arising from the buried Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. I was first drawn to their histories as a child when the abuse was ongoing, perhaps because I sensed in them mirrors of my own experience. I’ve been deeply absorbed by them ever since.

Taking us beyond injury into healing, found materials from Pompeii and Herculaneum seed all the poems I’ll share with you. ‘o dog of pompeii’, which opens bird of winter, includes a plaster cast of a guard dog, and the charm bracelet found on a child in Herculaneum. Engaging with them let the poem rise up and take flight. The dog is below, and the charm bracelet concludes this piece.

Erasing an epigram by the Roman poet Martial, that featured before and after images of Vesuvius, allows me to honour the beauty inherent to my body and spirit as a child. It also suggests what was done to me.

In bird of winter, the pyroclastic flow from Vesuvius is a recurring expression of the onslaught of sexual abuse. The rock, into which that volcanic ash and debris hardened, solidifies also into the difficulties I meet, trying to dig down into my past. Against this, three shrines rescued from Herculaneum’s harbour, hold energies which sustain my spirit. Through them, I was ultimately able to face down what sought to destroy me.

The poet Statius was born near Vesuvius. His work helped frame my reflections on what it means to live beyond rape in childhood. Written a decade after the volcano erupted, a fragment in his long poem Silvae imagines when the landscape will have healed, but asks what this new growth could hide. I translated his Latin and then interleaved our couplets.

As happens for many abused children, while I was growing up, and the crime was ongoing, most people around me looked away. Aged thirteen, I was hospitalised weighing twenty-eight kilos.

Water is my healing element. I cleanse and rediscover my body with every immersion, every length I swim. Photos of a mosaic found in the House of the Faun in Herculaneum were the starting point for ‘sea level’.

The image above is of the charms taken from the ‘burnt child’ found on Vesuvius’s shoreline in ‘o dog of pompeii’. She was awaiting rescue with others in the harbour area. Many were good luck charms, presumably collected for her by family members who loved her and wished her well in her life, at least until that fateful day when the volcano began to erupt. The child was also holding the beautiful vase photographed below them. These objects moved me deeply when I saw them, because they gave us back her life, and her humanity, and the tenderness in which she was held. When I wrote the poem, these objects nestled a kernel of hope into the harsh images of what was done to me.

This hope is also present to those people currently trapped in Gaza, as they fight to stay alive day after determined day, as they have had to for so many years now. The last poem I’ll read comes close to the end of bird of winter. The force of the volcano has been reclaimed to represent the energy needed for change. With it, we stand at last in a place of healing and growth.

The poems quoted are all from bird of winter, published by Pavilion Poetry, who are ten years old this year.