From October 2028 – seven years now, and counting – I’ve been part of a loose affiliation of poets who work with complex materials. Drawing together our earliest members, my hope was to create a group whose participants would co-resource each other. I wanted us to collaborate creatively, and editorially, but also offer mutual support – especially where confidence and courage, and above all, tenderness, might be needed. What we had, and still have, in common was knowing that we were working with materials that had the potential to be dangerous to us, and to each other. Together, we enact our shared commitment to go gently as we allow new work to take shape. Many of us work with our individual experiences as starting points to travel outwards towards the world, and inwards towards the wider histories and geographies that have embedded themselves within our spaces of being and are ask to be spoken to and of.

While work always originates with the maker who creates it, since that autumn evening in 2018, many collections, and pamphlets, including my own debut bird of winter, have gained strength and momentum through being brought, one poem at a time, to our group’s monthly meetings. We started out above the Poetry Café in Betterton Street in Covent Garden, then moved to the foyer of the National Theatre on London’s Southbank, waiting for the audiences to take their seats before getting down to our feedback. Having gone online during the pandemic, we have stayed there ever since, freed from geographical restrictions.

In different ways, all of us have been nourished by the conversations around process, and working practices, which open every session. The privilege of meeting each other’s works in progress, and giving them our careful responses, has been powerful and generative. Natalie Whittaker, Wendy Allan and Mary Mulholland have all engaged at different times with the group. When I heard they were planning to share a reading at The Poetry Café, I was thrilled to be asked introduce them. It seemed like a true celebration to hear their work and voices out loud and proud, two floors down from where our group began.

The evening didn’t disappoint. In fact far from it. Going to places where many might fear to tread, Mary Mulholland, Wendy Allen, and Natalie Whittaker make poems to hold the central acts of our lives. Through their words, we live, love, bleed, heal – and meet life towards its endings, as well as its beginnings. The audience’s warm engagement with their passionate, wry, fiery readings, and the conversations we had about the poems following on from them, made me want to share something of that evening with a wider audience.

What follows are my introductions, and videos of Mary, Wendy and Natalie reading their sets, which they filmed individually at home afterwards. At the time publication, Wendy’s was still on its way. The blog finishes with a question from me for each of them, engaging with a theme that’s central to their practice. I’ve also included the all-important buy-links within the titles of their books, so you can go deeper, and support them, and, the publishers bringing this essential work onto the printed page and into beautiful bound volumes.

Mary Mulholland reading at the Poetry Cafe.

A few words about Mary Mulholland, now, before the video of her reading. Her first two publications were both collaborations with Vasiliki Albedo and Simon Maddrell, published by the inimitable Nine Pens. All About Our Mothers led the way, with its logical sequel, All About Our Fathers, following. Both acid-sharp pamphlets. Her first solo pamphlet, the wonderful, not entirely woolly, What the sheep taught me, then came out with Live Canon in 2022. Most recently the elimination game, published this year by Broken Sleep. Rebecca Goss hailed it as “an illuminating, fearless study of the rich intricacies of female life”. Beyond Rebecca’s tribute, Mary Mulholland is widely published. More recently her poems have appeared in 14 magazine, Anthropocene, Stand, and are forthcoming in Finished Creatures. Mary also founded the generative and nurturing, live and online gathering, Red Door Poets, and is Editor of The Alchemy Spoon.

Speaking more personally, for me one of the delights of Mary’s penetrating poems is how they encompass adventure and irreverence as life-giving energies, but then move in a heartbeat to questing, questioning vulnerability. Time is folded and unfolds itself from moment to moment, as we move from a “kohl-eyed girl in a purple kaftan” to a “bronze age mummy” smelling of “honey scent and sweet bark”. Elsewhere an older woman enters an arctic whose cold “takes her back to childhood,” only for the mood to shift again as we come upon “a cluster of Parisian grandmothers” who are “elegantly chatting and laughing”, entirely oblivious to their charges’ high risk play choices.

Here’s Mary Mulholland’s ‘Woodstock’ from the elmination game as a bonus.

Our next reader was Wendy Allen, who shot, more or less fully formed, into the poetry firmament, after a first career in aviation. Early on, Caroline Bird hailed how “reading Wendy Allen’s poetry makes me realise there is a precision to the erotic, every line feels like a held breath.” Wendy’s debut pamphlet, Plastic Tubed Little Bird, was published by Broken Sleep, in 2023. She has since collaborated with Charley Barnes on freebleeding (Broken Sleep 2024) and Galia Admoni, i get lost everywhere, you know this now (Salo, 2024). Most recently, we have Portrait in Mustard from Seren. All are magnificent, and unmissable. Wendy’s currently in the final year of her Creative Writing and Art History PhD and is a tutor in Contemporary Poetry at Manchester Met.

Wendy Allen reading at the Poetry Cafe.

I love how Wendy’s work is centred on, and translated through, the variously fertile female body, and its desires, and despairs, often calibrated relative to made artworks and consumable objects. In ‘Apricot’ the narrator ends up inside the said fruit only “the stone is missing, and I am/ curled up in the pit where/ time should be.” Moving through such landscapes, Wendy’s poems creates a magic lantern play of shadowed and projected selves. They rise up and deliquesce away, even as their “nipples tiara against an/ endlessly repeated new-start sky.”

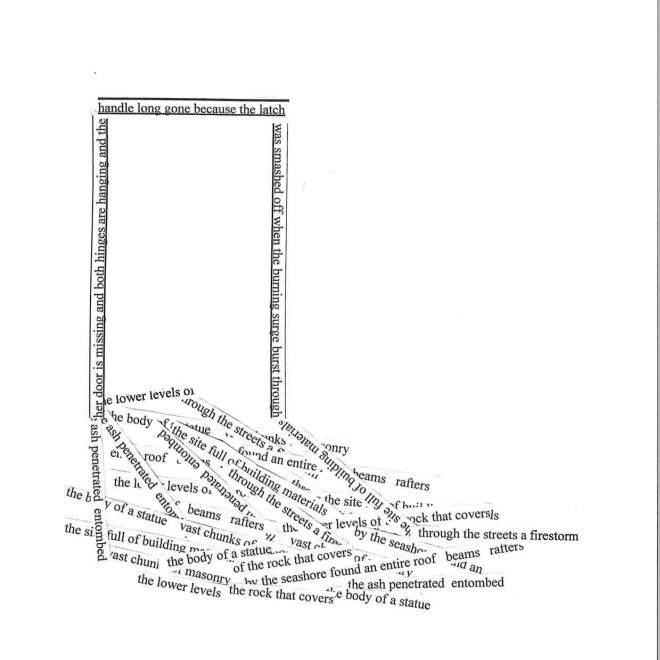

Finally, our third reader was the extraordinary Natalie Whittaker, celebrating the launch of The Point is You Are Alive, her heart-stopping first full collection which came out with Broken Sleep in April this year. As many of you know, Natalie writes with a spareness and precision that allows her poems to vibrate with imagistic intensity. Writing for the Poetry School, Jonathan Edwards admired the way “elegant sentences and striking images cast enormous shadows, conjuring something much bigger than themselves.”

Natalie Whittaker reading at the Poetry Cafe.

Integral to the work she makes are Natalie Whittaker’s roots in South East London. A poet and teacher, she is the author of two stunning previous pamphlets: Shadow Dogs, published by ignition press in 2018, and Tree, published by Verve in 2021. Natalie was also a London Library Emerging Writer from 2020 – 2021.

Deeply embedded in landscape and place, Natalie’s poems often ask us to see visually, as a starting point to participating in an act of shared perception. In SANDS, facing the loss of a child, “it is November I steer headlights through drizzle / pull up outside a church that’s switched off”. Earlier, there had been a “ghost dog […] beneath the ice”. Finally, and redemptively, comes SPRING “in a contagion of blossom/ a pink blooming pandemic” – where, paradoxically, life can start again.

Here’s Natalie Whittaker, reading her specially recorded poems.

And this is a ‘Jenga’, from Natalie’s set.

To close, the three questions, which transitioned us from the live readings into a wider discussion with the audience. It’s always so powerful to hear poets speaking about the making and thinking of their work, bridging the gaps between the creative energy as it first came to them, and the shapes it forms on the page.

Firstly, a question for Mary Mulholland.

ah: You’re a savagely witty, wry writer in a way that is pure delight for your readers. Tell us about humour as a lightning rod shooting us deep into the complex heartlands of your work? In short, why so wry?

MH: I suppose I find people behave in funny ways. The disjunct between what they say and do. Our secret lives. And life/ fate has its own sense of humour, which is not always kind, but perhaps serves as a reminder that things are always changing. I never set out to be funny so I guess it’s ingrained – I have a fairly existential approach. Life’s taught me there’s much that one should not take too seriously. Seeing the ridiculous or ironic in difficult situations can ease the tension and laughter is infectious, it connects us, releases endorphins, transforms, breaks through, like shining a light in the dark.When my father who was so sharp and accomplished developed dementia, the subsequent crazy conversations we’d have ironically enabled me to get to know him better, as if a lid had been lifted from his controlled way of being. It’s irony mainly that I enjoy. Humour is a bit like playing with fire. Of course not everything can or should be laughed at, but without humour life would be very heavy going.

ah: Wendy, as you write her, the female self is infinitely expansive, imaginatively, physically, and aesthetically. Also witty, and hungry. Tell us more about working through seemingly individual female experiences as portals to something much larger. In short, why so radical?

WA: Why so radical? A conversation.

Dear alice, Mary, and Natalie,

I’m writing this at the onset of my period. I am so tired I feel like I’m filled with lead.

You may, at this point, be questioning why you need to know this. You need to know this because I write what I am, and what I currently am is a body about to bleed.

I have just started teaching at a university, and one thing I repeat to my students, is the value of feeling the poem – to understand our bodily response to the poem – to its visuals -to its (the poem’s) body.

Recently in the news it has been reported there has been research into how visiting a gallery and looking at art is beneficial to our health.

I think the same about looking at the poem.

I love looking, and by that, I mean really looking, at poems, just as I like looking at my menstrual cup, just as I like looking at the sculptures of Barbara Hepworth (and we all know I like that).

My poetry is not a book of hidden desire. It doesn’t mute desire or mask its own pleasure. All my books speak of desire with pride. They paint desire on a huge canvas and make pleasure so large that when you walk past it in the gallery-that-is-a-book, you are unable to not see it. The fact that sometimes, my poetry may provoke a response which questions its necessity, simply highlights that there is a need for this. I think of Eileen Myles here. I love writing like this.

In answer to your question, alice, why so radical? Because it makes me sad when I see bestselling books of women sharing their fantasy as a hidden desire. In Portrait in Mustard (Seren Books, 2024) the speaker of my poems uses poetry to display her pleasure, her disappointments, her sex as her art. She wants to flaunt this –

In April 2024, I attended the For Art History conference at York University. On the final day there was a panel on the work of Art Historian Griselda Pollock, and at the end, Pollock gave her own response to the papers.

I will never forget that in her introduction to the lecture, Pollock acknowledges the work of the panel but raises the point that her work’s impact should not be viewed as a singular, rather, because of the community of women she worked alongside, whose belief and desire for change, collectively changed feminism in art history, and the wider sphere. Radical practice involves collaboration. It is incredibly important to me to address this notion of change through my poetic practice.

At the recent reading at the Poetry Society in Covent Garden with yourself, Mary and Natalie, our conversation reminded me that collectively, we can achieve so much. Our practice may differ, our poetry may be thematically different, but when we are together, when we share our work and engage with each other, as we do within our Stanza community, that, then, is where the change happens. That is where we are at our strongest.

Wendy x

ah: Natalie, your collection holds some tough material, around societal harms, and the profound loss of stillbirth. At every turn, though, your poems pulse with fierce life, and an intensity of being that sees off their darknesses. In short, where does the joy come from?

NW: The joy comes from writing poetry; the joy of playing with language and experimenting with form. Even though the subject matter of my poems is often something that has troubled me in some way, there is usually a real joy in the act of writing a poem. The ‘Tree’ sequence is an exception, as I can’t honestly say that I ‘enjoyed’ writing those poems. But there’s a different sort of joy in those poems; a slow-burning joy that comes from transforming painful experiences through art, and the joy of sharing my work with others who may be going through something similar.